Businesses often fail during growth: costs rise faster than revenue, processes break under pressure, and what used to feel lightweight and fast-moving turns into ongoing operational fire drills.

In fact, research consistently shows that growth and complexity go hand in hand. Companies like Meta and Google often acquire instead of building internally to gain speed, synergies, and immediate capabilities, a strategy applicable across scales (Altimi). Fast-scaling firms pursue add-on acquisitions for synergies but struggle with integration complexity.

Mergers and acquisitions activity keeps accelerating in many industries as companies buy a scalable system instead of building it from scratch, and integration strategy becomes one of the biggest factors behind whether those deals create value—or destroy it.

That’s why the conversation about vertical vs. horizontal integration is not theoretical—it’s a practical decision about how you’ll scale:

- Do you expand by acquiring competitors and increasing market share?

- Or do you expand by owning more steps of your supply chain and improving control?

In this guide, we’ll break down both strategies, show real-world examples, and help you choose the right path based on cost, speed, risk, and operational reality.

1. Horizontal integration and vertical integration are two core growth strategies.

2. Horizontal integration focuses on expanding market share by combining similar businesses at the same stage of the value chain.

3. Vertical integration focuses on increasing control by owning additional stages of the value chain and operations.

What Is Horizontal Integration?

Horizontal integration is a growth strategy where a company expands by acquiring, merging with, or building operations that exist at the same level of the value chain—typically by combining with a competitor or a similar business in the same industry.

In practice, horizontal integration is often implemented through horizontal consolidation, where companies combine similar businesses to increase market share, reduce competition, and achieve economies of scale.

In simple terms:

Horizontal integration = getting bigger by adding “more of the same.”

That could mean:

- a retailer buying another retailer,

- a marketplace acquiring another marketplace in the same niche,

- a manufacturer buying a competing manufacturer,

- an eCommerce brand purchasing a competing brand with a similar audience.

The goal is usually to increase market power, expand customer reach, reduce competition, and improve cost efficiency. This approach can deliver faster access to scale than organic growth.

In many industries, horizontal integration is a response to market consolidation: companies combine to defend margins and strengthen positioning.

Key characteristics of horizontal integration:

- Same product type

- Same customer segment

- Same part of the value chain

- More market share, more scale

For example, if you run a multi-store eCommerce business and you acquire another store selling similar goods to the same audience, that’s a clear example of horizontal integration.

In the eCommerce world, horizontal integration often looks like:

- buying a competitor’s online store,

- launching a second brand under the same business model,

- acquiring a regional player to enter a new market faster,

- combining two catalogs to create a stronger category leader.

Discover what it takes to scale marketplaces across regions and countries: Global Marketplaces.

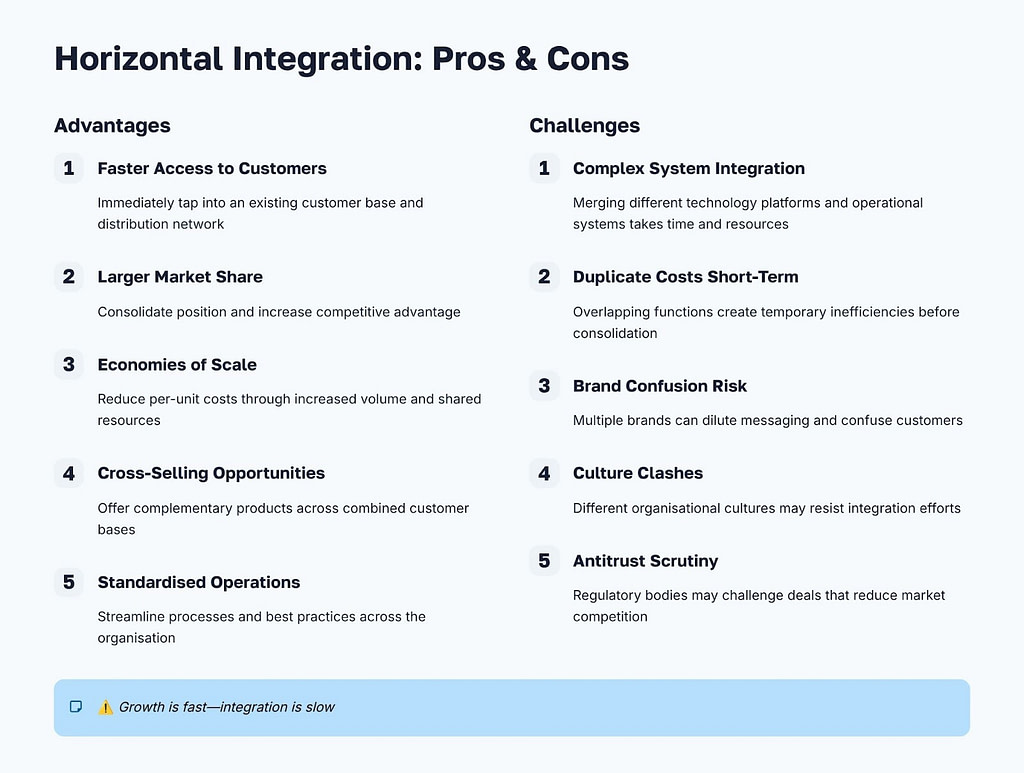

Pros and Cons of Horizontal Integration

Horizontal integration is popular because it can generate fast growth. But it also comes with risks—especially operational and regulatory ones.

Pros of Horizontal Integration

1) Faster growth than organic expansion (time-to-scale). Acquiring an existing business often gives you instant access to:

- customers,

- revenue streams,

- supplier contracts,

- proven product-market fit.

2) Bigger market share and stronger positioning. When you remove competitors from the market (or merge with them), you gain leverage:

- against suppliers,

- against distribution channels,

- and even against marketplaces and ad platforms.

3) Economies of scale (lower unit costs over time). With higher volume, you can often reduce:

- fulfillment costs per order,

- customer support cost per ticket,

- procurement costs,

- marketing overhead and tooling costs.

4) Stronger brand visibility and cross-selling opportunities. Two similar businesses can cross-sell to each other’s audiences through:

- email marketing,

- retargeting,

- bundle offers,

- shared loyalty programs.

5) Operational standardization. Over time, you can unify processes:

- pricing rules,

- product information management,

- inventory planning,

- customer service workflows.

Cons of Horizontal Integration

1) Post-merger integration is harder than it looks. Merging two businesses means merging:

- teams,

- systems,

- policies,

- reporting definitions and governance,

- and customer experience.

The customer-facing model may look similar, but internally it rarely is. Without a clear integration plan, synergy realization often stalls, as overlapping teams, systems, and processes remain fragmented.

Learn more about multisites from our post: Multi-Store eCommerce: What, Why, and How It Will Help Your Business

2) Duplicate costs (until you consolidate). At first, you may temporarily pay for two of everything:

- warehouses or fulfillment partners,

- marketing tools,

- CRM systems,

- customer support teams.

3) Brand conflict and customer confusion. If both businesses sell similar products, customers may ask:

- “Which brand is the real one?”

- “Why are prices different?”

- “Why are policies inconsistent?”

4) Culture clashes and employee churn. A common reason horizontal acquisitions fail—is people. Different cultures and leadership styles can slow execution and create internal resistance.

5) Regulatory and antitrust risk. In many markets, acquiring competitors can trigger investigations, especially if the combined company starts dominating a category or region.

Horizontal Integration Examples

Horizontal integration happens at every level—from global enterprise deals to growing eCommerce businesses buying smaller competitors. Here are some real-world examples.

Retailer Buys Retailer

Dick’s Sporting Goods acquired Foot Locker for $2.4 billion, finalized in September 2025.

Both sporting goods retailers gained over 2,400 stores across 26 countries, pushing combined revenue toward $21 billion.

Marketplace Acquires Marketplace

Etsy bought Depop, a fashion resale marketplace, for $1.625 billion in 2021.

Depop added 30 million users to Etsy’s creative goods platform, both connecting sellers of vintage apparel.

Manufacturer Buys Competitor

Honeywell acquired Carrier Global for $18.6 billion in 2025.

Competing HVAC manufacturers merged production lines for efficiency and tech advancements in climate control.

eCommerce Brand Buys Competitor

Grove Collaborative purchased Grab Green’s assets in February 2025.

Both eco-friendly cleaning eCommerce brands shared sustainable audiences, enhancing Grove’s home care portfolio.

What Is Vertical Integration?

Vertical integration is a growth strategy where a company expands by taking control of more steps in its value chain—the stages it normally relies on partners, suppliers, distributors, or third parties to handle.

In simple terms:

Vertical integration = getting stronger by owning “more of the process.”

Instead of only focusing on selling a product, a vertically integrated business may also control parts of:

- manufacturing

- sourcing and procurement

- warehousing and fulfillment

- distribution channels

- retail storefronts (online and offline)

- after-sales service and returns

- even data and customer relationships

Vertical integration often becomes relevant when a company reaches a point where outsourcing starts creating friction: too many delays, too little control, rising costs, or inconsistent customer experience.

Key characteristics of vertical integration:

- Same industry

- Different stages of the value chain

- More control, fewer dependencies

This is the opposite logic of horizontal integration. Horizontal integration is about scale and market share. Vertical integration is about control and efficiency.

In eCommerce, vertical integration often means building a business model that’s less dependent on:

- marketplaces

- distributors

- fulfillment providers

- third-party logistics constraints

- external manufacturers

- inconsistent supply chain data

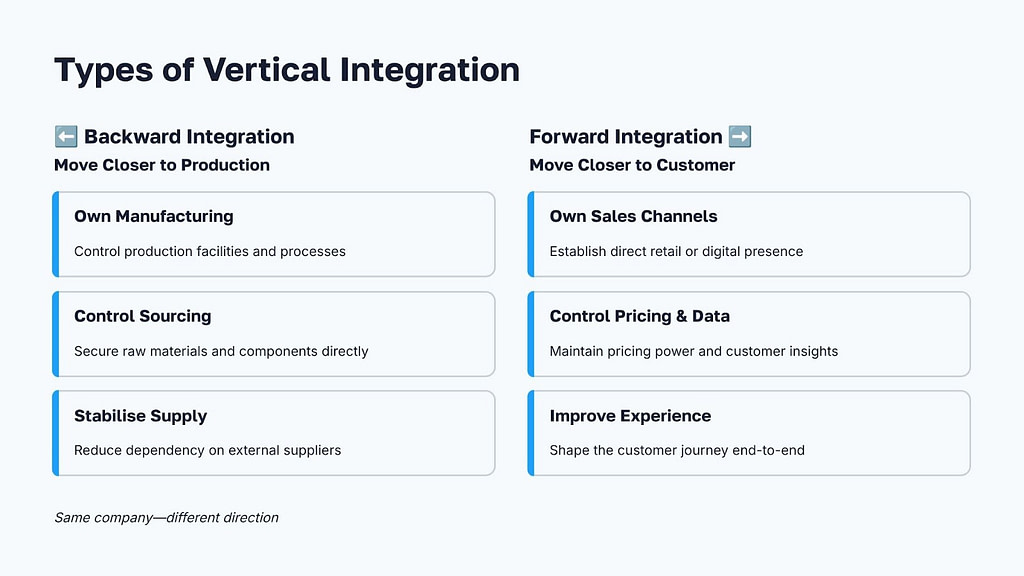

Types of Vertical Integration: Forward vs. Backward

Vertical integration can happen in two directions—depending on where you move in the supply chain.

1) Forward Vertical Integration (moving closer to the customer)

Forward integration happens when a company expands toward the end customer by taking ownership of distribution or retail, a model often referred to as downstream integration..

Example moves include:

- a manufacturer launching a direct-to-consumer (D2C) online store

- a wholesaler building its own B2B portal for recurring buyers

- a brand opening its own marketplace or retail platform

- a company building its own last-mile delivery capability

- a supplier launching a branded storefront instead of selling only through resellers

Why does it happen? Because customer access is key. When you own the sales channel, you own:

- customer relationships

- pricing strategy

- product positioning

- marketing data

- repeat purchase mechanics

In practice, forward integration is often a response to platform dependency: “We don’t want to rely on marketplaces and resellers forever.”

2) Backward Vertical Integration (moving closer to production)

Backward integration happens when a company expands upstream by owning the production or sourcing side of the business, a model often referred to as upstream integration.

Example moves include:

- a retailer acquiring a manufacturer

- a brand producing its products instead of using a contract manufacturer

- a company building a private-label supply chain

- a marketplace or large seller buying upstream capacity to stabilize inventory

Why does it happen? Because supply stability is a competitive advantage. If you control production or sourcing, you reduce:

- stockouts and delays

- quality issues

- unpredictable costs

- dependency on suppliers

Backward integration is often triggered by the painful reality of scaling: “Demand is there, but supply keeps failing us.”

See how eCommerce platforms reshape supply chains, control, and scalability in our article: What’s the Role of eCommerce in Supply Chain Management.

Pros and Cons of Vertical Integration

Vertical integration is powerful—but not “free.” It usually improves long-term resilience, but increases operational complexity.

Pros of Vertical Integration

1) More control over quality, speed, and customer experience. You can standardize the end-to-end journey:

- packaging quality

- delivery speed

- support and returns

- product availability

- brand consistency

Instead of constantly negotiating with third parties, you can improve the system internally.

2) Stronger margins (when executed well). By removing intermediaries, companies may reduce margin leakage and control pricing more effectively.

This is especially relevant for:

- fast-moving D2C products

- high-repeat categories (consumables, beauty, health)

- specialized B2B supplies with predictable demand

3) Better supply chain resilience. Owning critical parts of the chain helps reduce disruption risk from:

- supplier shortages

- logistics bottlenecks

- policy changes

- cost spikes

4) More predictable operations and planning. Vertical integration can reduce chaos by allowing better forecasting:

- stock levels

- lead times

- replenishment cycles

- production capacity

5) Data advantage and operational clarity. When systems are connected under one umbrella, you get better decision-making:

- real demand signals

- product performance by channel

- accurate inventory status

- fewer “black box” processes

This matters significantly when you want to scale beyond a single storefront into:

- B2B portals

- multi-storefront ecosystems

- marketplaces

- omnichannel operations

Cons of Vertical Integration

1) Higher operational complexity. You’re no longer “just selling.” You’re managing multiple business functions, such as:

- procurement

- manufacturing

- fulfillment

- compliance

- customer service

More control = more responsibility.

2) Higher upfront investment. Vertical integration often requires real capital:

- warehouses or logistics contracts

- production tooling

- hiring operations specialists

- software and integrations

3) Less flexibility in the short term. Once you own a warehouse or manufacturing line, you reduce short-term agility due to fixed-cost commitments. Your fixed costs increase, and your system becomes harder to change quickly.

4) Execution risk (it fails if operations aren’t mature). A business can lose money “while vertically integrating” simply because:

- they underestimated the complexity,

- their tech stack can’t support the new processes,

- or the team isn’t ready to operate at that level.

5) Potential distraction from core strengths. Some companies integrate vertically too early and lose focus. Instead of doubling down on product, marketing, and growth, they get pulled into operations and infrastructure.

Vertical Integration Examples

Here are several examples of vertical integration that clearly show how the strategy works in real life.

Brand Builds eCommerce Storefront

Nike launched its direct-to-consumer Nike.com and apps in the 2010s, shifting from heavy reliance on retailers like Foot Locker.

By 2025, direct sales hit over 40% of revenue, enabling custom branding, data capture, and higher margins by reducing third-party take rates.

Retailer Buys Manufacturer

Walmart acquired select food suppliers like Paramount Farms in 2013, later expanding into private-label manufacturing for groceries.

This backward move secured supply amid shortages, cut costs by 15-20%, and ensured quality for its 10,000+ stores.

eCommerce Builds Fulfillment

Amazon evolved from third-party logistics to Amazon Fulfillment (FBA) in 2006, now handling 60%+ of its sales volume in-house.

Prime speeds deliveries to 1-2 days, supports bundles/returns, and scales across 20+ countries for multi-storefront growth.

Marketplace Adds Services

Etsy integrated payments, shipping labels, and Depop’s vendor tools post-2021 $1.625B acquisition.

This forward step streamlined 30M+ users’ transactions, reducing disputes and external dependencies while keeping the platform core.

B2B Builds Procurement

Alibaba added account pricing, ERP syncs, and invoicing via Cainiao logistics and 1688.com by 2023.

Clients now manage bulk orders seamlessly, shifting Alibaba from listings to full procurement ecosystems across industries.

Vertical vs. Horizontal Integration: Key Differences

The simplest way to separate these strategies is this: horizontal integration helps you grow wider by combining with similar businesses at the same stage of the market, while vertical integration helps you grow deeper by taking control of more stages in your supply chain and operations.

Horizontal vs. Vertical Integration Comparison Table

| Factor | Horizontal Integration | Vertical Integration |

| Operating logic | Expand by adding similar businesses | Expand by owning more steps of the value chain |

| Main goal | Market share + scale | Control + efficiency + resilience |

| Typical move | Acquire/merge with a competitor | Acquire/build suppliers, logistics, distribution, retail |

| Value drivers | Bigger reach, reduced competition, economies of scale | Better margins, fewer dependencies, higher service quality |

| Operational impact | Consolidation and standardization | Expanded operating scope and process ownership |

| Speed of results | Often faster (growth looks immediate) | Slower (requires execution and process maturity) |

| Primary risks | Integration + culture + redundancy risks | Complexity + investment + capability risks |

| Best for | Winning in a crowded market | Stabilizing quality and removing bottlenecks |

| Typical trigger | “We need more customers, faster” | “We need more control and predictability” |

Learn how marketplace integration strategies differ and when each model makes sense: Horizontal vs. Vertical Marketplace.

When Horizontal Integration Works Best

Horizontal integration is usually the better strategy when your primary constraint is go-to-market reach, not supply chain control.

It works best when:

- The market is fragmented, and consolidation creates a clear advantage (many similar players, no dominant brand)

- You can gain customers faster through acquisition than through marketing (especially when CAC is rising)

- You want to enter a new region quickly by buying a local player with an existing audience and operations

- You have strong operations already, and you can absorb another business without breaking execution

- Competitors are slowing you down and removing them increases pricing power or category leadership

Rule of thumb: If the bottleneck is demand and positioning, horizontal integration often wins.

When Vertical Integration Works Best

Vertical integration works best when your biggest growth constraint is external dependencies: suppliers, logistics, production capacity, or lack of channel control.

It makes the most sense when:

- Quality or delivery is your competitive advantage, and third parties keep breaking it

- You’re losing margin to intermediaries, and you want long-term profit stability

- Your supply chain is unstable, and stockouts or delays are limiting growth

- You’re scaling into new models like:

- B2B sales with contract terms

- multi-storefront ecosystems (brands / regions)

- marketplaces with vendor management and payouts

- You want to own the customer relationship instead of relying on third-party platforms or channel partners

Rule of thumb: If the bottleneck is control and predictability, vertical integration often wins.

Explore the most common marketplace models and how they impact growth and monetization in our Guide to Marketplace Business Models.

Challenges and Risks of Both Strategies

Both strategies can create huge value—but only if execution matches the strategy. Most “integration failures” don’t come from choosing the wrong direction. They come from underestimating complexity.

In practice, integration fails when companies don’t define a single operating model early: decision rights, ownership boundaries, escalation paths, and governance mechanisms across the combined organization.

Operational Complexity

Even the best integration plan becomes risky if your organization isn’t ready to operate at a new level.

Common operational problems include:

- unclear ownership and decision rights (“who’s responsible for what now?”)

- duplicated teams and processes

- inconsistent customer experience across brands or channels

- slower decision-making due to added layers

Horizontal integration tends to create complexity through consolidation. Vertical integration creates complexity by adding entirely new responsibilities.

Technology and Data Integration Issues

Technology is one of the most underestimated risks in both strategies. Integration often fails because systems don’t match—and manual work explodes.

Typical issues:

- customer data split across platforms (CRM, email service providers, support tools)

- different product data structures and catalog logic

- mismatched pricing rules and discount policies

- reporting becomes inconsistent (“which numbers are correct?”)

- inventory sync breaks, causing overselling or stock inaccuracies

- integrations with ERP / PIM / accounting / warehouses require redesign

Without unified systems, inventory optimization becomes nearly impossible, as fragmented data leads to inaccurate stock visibility and replenishment decisions.

This is where businesses usually hit the wall: “We merged the companies, but we didn’t merge the systems.” This is why mature organizations treat integration as a structured post-merger integration (PMI) program, with a clear Day 1 setup, Day 30 stabilization, and Day 100 operating model alignment.

Simtech Development has integrated systems for eCommerce companies since 2005. We assess requirements, data models, and APIs, produce field-level mapping and transformation specs to align fields (e.g., products, orders, customers) between platforms like CS-Cart, Shopify, QuickBooks, or ERPs, and then implement custom or pre-built connectors for reliable, auditable synchronization.

Legal and Regulatory Risks

The legal risks depend on the type of integration—but they can be serious in both cases.

Horizontal integration risks:

- antitrust scrutiny (especially if market share becomes too high)

- regulatory objections to mergers and acquisitions

- restrictions in certain countries or categories

Vertical integration risks:

- compliance requirements across more operational areas (logistics, payments, product safety, taxation, cross-border trade)

- vendor and supplier contract renegotiations

- liability increases because you own more stages of delivery and service

The bigger the system you own, the more rules you have to follow—and the more expensive it is to get compliance wrong.

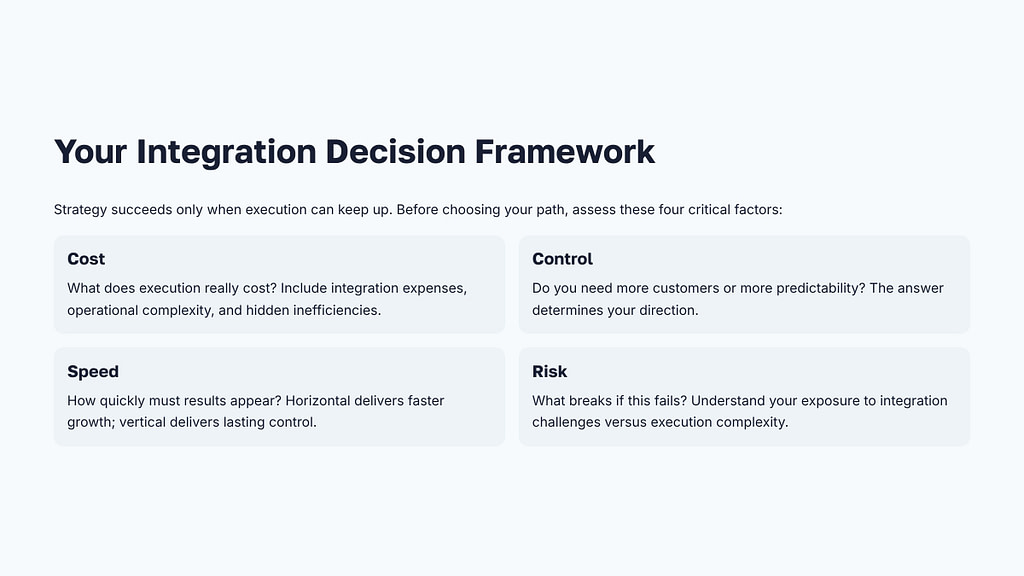

How to Choose the Right Integration Strategy

Choosing between vertical and horizontal integration isn’t about picking the “smarter” option. It’s about choosing the strategy that removes your biggest growth bottleneck right now—without creating a bigger operational mess six months later.

A practical decision framework is based on four factors: Cost, Control, Speed, and Risk.

If your primary constraint is control, supply reliability, or margin stability, vertical integration is usually the better fit.

At the enterprise level, this decision should also be grounded in measurable outcomes: synergy targets, integration costs, and time-to-value. Without clear KPIs, integration success becomes subjective and hard to manage.

Get a realistic breakdown of marketplace launch costs and hidden expenses from: What’s the Cost of Launching an Online Marketplace.

Key Factors to Evaluate: Cost, Control, Speed, Risk

1) Cost: What will this expansion really cost you?

Integration strategies often look profitable on paper—but the real cost is usually hidden in execution. Beyond acquisition price, companies should account for transaction costs, integration overhead, and short-term cash flow pressure during consolidation.

Horizontal integration costs typically include:

- acquisition or merger costs (including due diligence)

- redundant roles and tools (until you consolidate)

- rebranding and marketing alignment

- platform consolidation and data migration

- organizational restructuring

Vertical integration costs typically include:

- building or acquiring new operational capabilities (fulfillment, manufacturing, retail)

- higher fixed costs (warehousing, equipment, staffing)

- hiring specialists to run operations you didn’t own before

- new systems, integrations, and compliance workflows

Quick way to think about it:

- Horizontal integration often costs more upfront financially.

- Vertical integration often costs more operationally over time.

2) Control: Do you need more customers—or more predictability?

Control is one of the biggest reasons companies move toward vertical integration.

Ask yourself:

- Are you losing money due to stockouts and late deliveries?

- Are suppliers limiting your ability to scale?

- Is inconsistent customer experience hurting retention?

- Are marketplaces or resellers controlling your relationship with buyers?

If the answer is “yes,” vertical integration can reduce dependency and improve stability.

But if your operations are stable and your problem is market reach, then horizontal integration usually creates more value:

- more customers

- more share

- more scale

3) Speed: How fast do you need results?

Speed matters because many businesses integrate as a response to urgency.

Horizontal integration can deliver faster growth results because you often acquire:

- revenue

- audience

- inventory

- operations

But speed can be deceptive if integration is not planned properly.

Vertical integration usually takes longer because you’re building capabilities you didn’t run before. The payoff is slower—but often more sustainable.

4) Risk: What can break if this goes wrong?

Both strategies carry risk, but in different ways.

Horizontal integration risks:

- integration failure (teams, processes, systems)

- culture clash

- customer confusion between brands

- overpaying for the acquisition

- regulatory restrictions

Vertical integration risks:

- complexity overload (you become a “different company” operationally)

- underestimating investment needs

- execution gaps (new processes, compliance, staffing)

- losing focus on core growth

A safe decision is usually the one where:

- your team can realistically execute,

- your systems can support the transition,

- and failure won’t threaten your core revenue.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Here are the mistakes companies most often make when choosing an integration strategy.

Mistake #1: Choosing a strategy while ignoring bottlenecks

Buying a competitor sounds exciting. Owning logistics sounds powerful. But if it doesn’t remove your real constraint, it won’t create value.

Mistake #2: Underestimating the operational load and integration governance

Integration involves months of decisions:

- catalog structure

- pricing rules

- fulfillment workflows

- customer service logic

- finance reporting

If your business already feels “busy,” integration will amplify that.

Mistake #3: Thinking technology is a small detail

Systems integration is often the hardest part:

- data mismatches

- broken processes

- inconsistent reporting

- manual work multiplying instead of shrinking

Mistake #4: Integrating too early

If your product-market fit is still unstable, integration will lock you into complexity before you’re ready.

Mistake #5: No plan for standardization after expansion

Integration only pays off when you consolidate:

- processes

- tools

- metrics

- responsibility

Otherwise you end up running two businesses with double the chaos.

Quick Decision Checklist

Use this checklist to quickly spot which strategy fits your situation.

Choose horizontal integration if:

- your operations are stable, but growth is slowing

- customer acquisition is expensive, and buying demand is faster than building it

- the market is crowded and consolidation creates advantage

- you want to enter a new region quickly

- you can absorb another business without breaking execution

Choose vertical integration if:

- suppliers, logistics, or fulfillment are limiting your growth

- you need consistent quality and delivery to protect your brand

- you want more predictable margins and less dependency

- you’re expanding into B2B, marketplaces, or multi-storefront operations

- you want to own customer experience end-to-end

Choose a hybrid approach if:

- you need market growth and more control

- you’re building an ecosystem (multiple channels, multiple regions, multiple models)

- you can manage complexity with strong operational leadership and the right tech stack

Conclusion: Which Strategy Fits Your Business?

Horizontal integration helps you scale wider—by growing market share and combining similar businesses. Vertical integration helps you scale deeper—by taking control of more steps in your value chain and removing bottlenecks caused by external dependencies.

The best choice depends on what’s holding your growth back today:

- If demand and reach are the problem, go horizontal.

- If control and predictability are the problem, go vertical.

- If you’re building an ecosystem, a hybrid strategy may be the most sustainable option.

And no matter which direction you choose, success depends on execution: aligning processes, technology, and teams around a single operating model.

If your integration strategy includes launching new sales channels, building multi-storefront operations, or evolving into a marketplace model, Simtech Development can help you plan and implement the transformation using CS-Cart software—from architecture and integrations to custom workflows and scalable infrastructure.

FAQ

The main difference between horizontal and vertical integration is the direction of growth. Horizontal integration means expanding by adding similar businesses at the same level of the market (often competitors). Vertical integration means expanding by taking control of more stages in your supply chain or distribution.

Horizontal integration often drives faster growth because it can bring immediate market share and revenue. Vertical integration often creates more sustainable growth by improving control, margins, and long-term stability.

Yes. Many companies combine both approaches over time—using horizontal integration to expand market reach and vertical integration to remove supply chain bottlenecks and improve execution. The key is sequencing it properly so complexity doesn’t grow faster than your business.